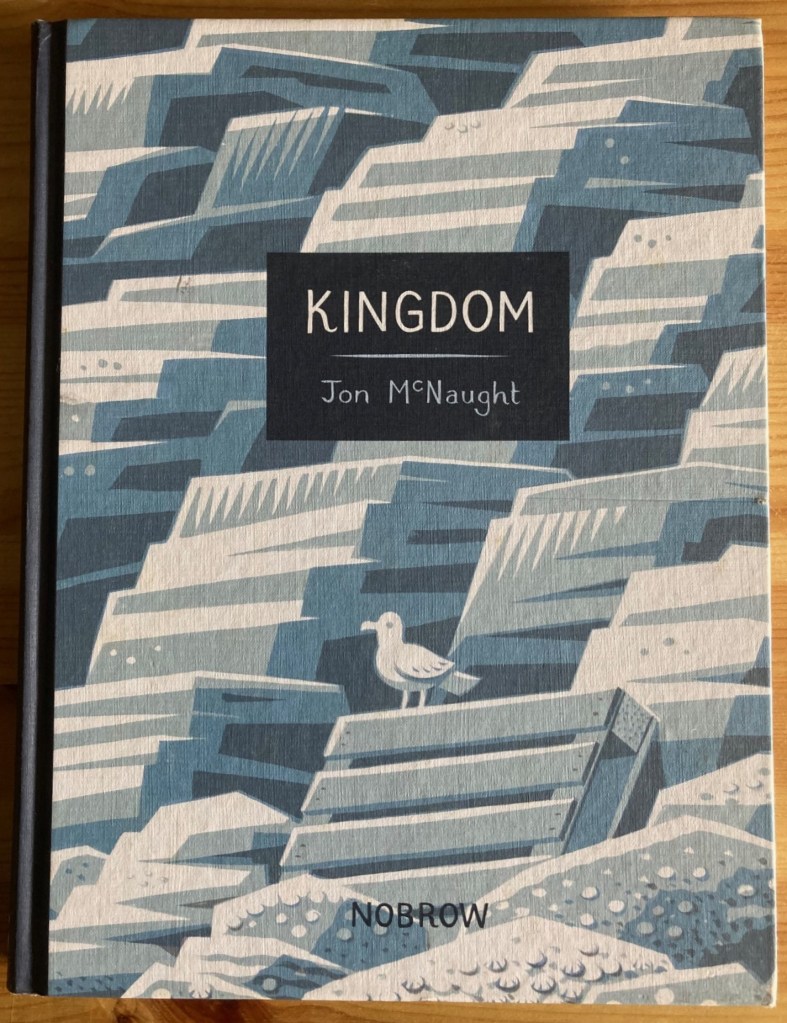

Jon McNaught, 2018

Read: January 2024

Edition Read: NoBrow, pages unnumbered

Graphic novel

In contrast to my other recent graphic-novel readings (The Road, Safe Area Gorazde, Ducks), Kingdom is not about crimes against humanity. It is far gentler, a slice of life, specifically, of a family holiday. Nothing dramatic or traumatic takes place. An unnamed mum and her two children (Andrew and Suzie) – the former a teenager, the latter around 10 – go on holiday to a caravan park somewhere on the British coast. It is understated and the pacing measured – as such holidays can be. It is a poignant snapshot of the parts of holiday that are rote, mediocre, uninspiring, and enforced fun that turn out to be anything but. Even the nature that surrounds Andrew and Suzie, the two protagonists, also becomes the minutiae of their life on holiday.

It is written in lots of very small panes, capturing a scene and all of its details (there are lots of onomatopoeias), shot by shot (up to 35 per page). The colour palettes are monochromatic hues of blues and reds, sometimes mixing together. There are relatively few words, and it takes several pages until someone talks.

It has its melancholic moments; I got the impression that the shot of the mother and Suzie driving away from Great Aunt Lizzie’s house is probably the last time they will ever see her, and despite Andrew making a friend (who is maybe a local, or perhaps someone just like him – on holiday and bored), there is a telling scene where they scorn a group of children, around their age, having fun in the distance. Whereas Suzie is still young enough to be curious about the world, Andrew seems to be keeping it at arm’s length, generally preferring to spend time alone or playing videogames. The mother is generally depicted as trying to do something for her children; at no point does she ever get to do anything for herself.

Although the whole point of the book is that not much happens, these memories, captured with all of their minute details, are the sort that will stay with the characters. How these children (and sometimes the Mum) relate to their environment is a big part of the story; the Mermaid’s Cave shows how memories can sometimes be better than the reality, but whereas Mum is disappointed about the reality when compared to her memory, Suzie likes it; and so the cycle continues. As such, Kingdom is about how we remember things. The caravan park that they stay at is called Kingdom Fields, but it is also memory that is a realm – a kingdom – in itself.

Worth reading? Yes.

Worth re-reading? Yes.