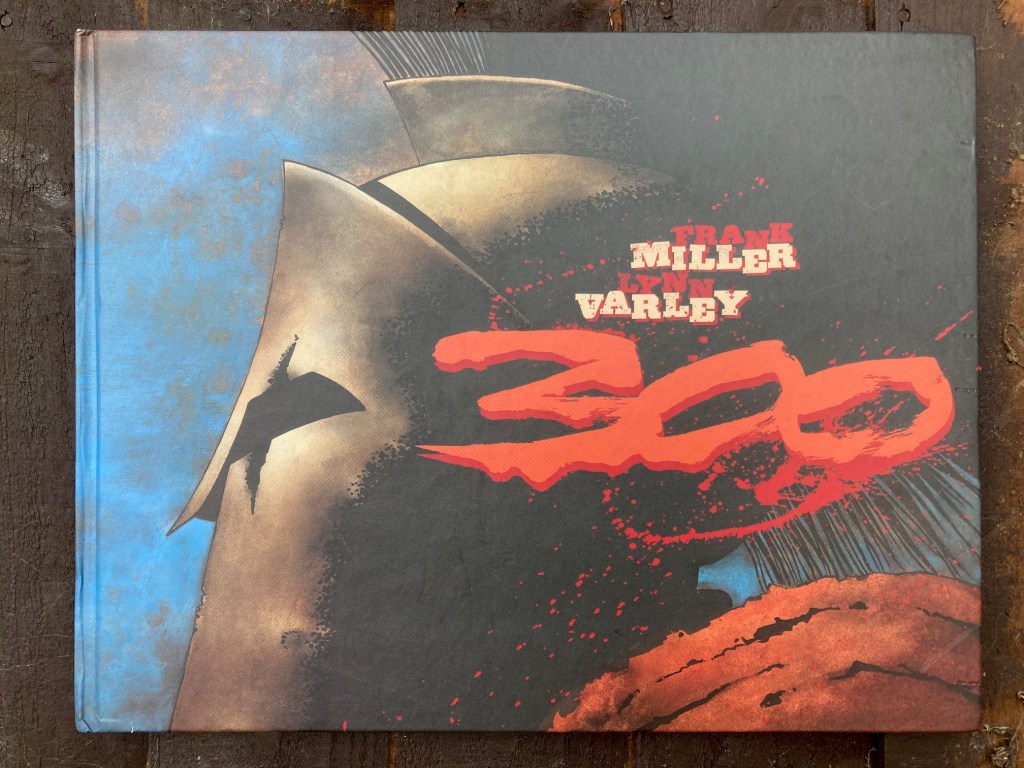

Frank Miller and Lynn Varley, 1999

Read March 2023 and re-read September 2025

Published by Dark Horse Books, 1999

Page count: not sure. It’s around a one-hour read.

Graphic novel, historical fiction

The blood-and-guts film adaption of this inspired every 17 year-old boy circa 2006 to actually believe that they would have held the Hot Gates. Since then, however, I’ve had the chance to mend my ways and reapproach this historic event via Tom Holland’s Persian Fire. Combined with a now fuller, not quite so heroic-mythical, less mental worldview and actually quite glad I am not a Spartan Hoplite*, let’s just say, Miller took certain liberties.

A Greek alliance (not Sparta alone) consisting of 7,000 troops, held the pass for most of the battle – not the titular 300 (which 300 does partially acknowledge). The 300 were the holding force left behind when the Spartan king and commander, Leonidis, realised they were about to be outflanked – well, plus the 700 Thespians who were written out of the story by Herodotus, the primary source for this period.** The Greek army was betrayed, but more likely by a shepherd who wanted his fields back from the logjammed Persian army (what’s Greek for ‘get off my lawn?’), than by a deformed pariah of Sparta, jilted at birth for being the weak link in the phalanx.

Now that the question of revisionism has been answered – is this a good read? Spartans, what say you?***

Well, citizen, the format of the book was well chosen, is the first thing they would say. Sized halfway between A4 and A3 landscape, it depicts the fighting and the landscapes of Greece in large scale. There is a lot of use of darkness, with features half-drawn with the other half blacked out – bodies, faces, cloaks, shields, rocks, piles of bodies – all the things you might expect to find at the Hot Gates. It’s a singular style and it’s easy to see Miller’s Sin City and The Dark Knight Returns in here and vice versa. It also gives an idea of the confusion of hand-to-hand fighting, with some panes take a couple of seconds to visually comprehend.

Starting in media res, the story moves along at a good pace and is well balanced, providing context about Sparta and why it was the way it was, complimenting the swords and sandals. The perspective is entirely Spartan – the Persians are given short shrift, depicted as the conscripted, decadent, undisciplined invading force of a foppish emperor, who ultimately can only win via underhand tactics. (The limited democracy of Sparta is underplayed and its subjugated neighbours go unmentioned.)

Read as a piece of fiction, it’s fine. Besides playing fast and loose with the facts of the event, it somewhat idealises Sparta, although any consideration that goes deeper than ‘those guys sure did kick ass’ should make it clear that it wasn’t a particularly fun place to live. The form of the hero’s journey is told in a way that feels like a story around a campfire, which, as a story drawn from the earliest history book, is fitting.**** It’s a bit short, at around an hours’ read, but this does serve to make it quite a punchy read. THIS WAS SPARTA (KINDA)!

Worth reading? Yes.

Worth re-reading? Yes – but now to hold the Hot Gates!

*Obviously Sparta of antiquity predates fascism as a philosophy, but there is a big overlap in ideas and practices between the two.

**Miller does include the Thespians in his telling, but rather than being part of the last stand, they surrender and are then immediately cut down.

***Go on. Make the noise.

****The Battle of Thermopylae was later set down in history by Herodotus (one of those ancient Greeks whose street cred eschews the need for a surname) in Histories, which is widely considered to be the first history book.