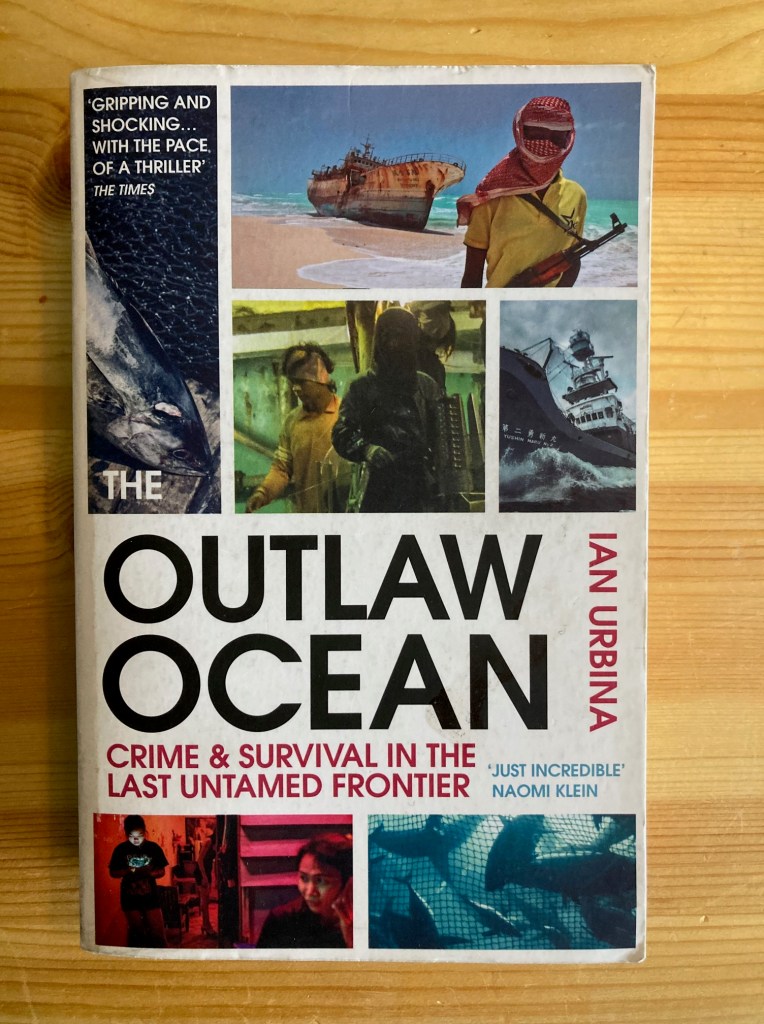

Ian Urbina , 2019

Non-fiction

Read: May–June 2025 (re-read from 2021)

Edition read: Vintage, 2020, 544 pages

Investigative journalism

Illegal fishing and whaling; under-resourced coastal authorities; vessels not fit for sea; human-rights abuses; abortions provided outside of national jurisdiction; stowaways castaway in the middle of oceans; slavers, slaves and unpaid mariners; repo men for stolen ships; oil explorations and environmental campaigners; waste disposal at sea and territorial disputes: Ian Urbina’s The Outlaw Ocean covers a litany of crimes and otherwise legally unclear practices at sea.

This is a highly readable book, combining an exhaustive approach towards small details with careful analyses of the big picture, which, chapter by chapter, rarely turn out to be black and white. Even when presenting a morass of details – sometimes legalistic, sometimes moral, sometimes technical – Urbina knows how to structure a story in a way that makes each of these 14 chapters captivating.

The chapters tend to fall into one of two categories: slightly more rote – but still highly engaging – matters, such as Palau trying to police fishing in its huge seas with limited resources, fishing vessels not fit for service sinking when trying to take in huge catches, people being trafficked to work at sea (there are a couple of chapters on this), oil exploration and environmental campaigning against it. The other category could be roughly phrased as ‘the unusual’ – the formation and continuing existence of Sealand, an organisation which provides abortions at sea on a dedicated yacht and the repo men who specialise in retrieving stolen ships.

Although it could have started with any of the chapters, Urbina plays it smart and starts with the thriller of Sea Shepherd chasing the illegal fishing vessel The Thunder through the Southern Ocean for nearly four months. Given that Sea Shepherd can be a polarising group, it was more nuanced than I expected, showing how groups of all shades sometimes chose to work with the law and sometimes outside.

It’s a chunky book but it’s never slow going; this is a re-read on my part, and should Urbina write any other books, I would read them based on the quality of this one. A bit of sailing on my own part has imparted the knowledge that the more time you spent at sea, the greater the sense that you know even less about it. In a kind of parallel to this more philosophical musing, one of the recurring themes from Urbina’s trips to sea, and present throughout Outlaw Ocean, is how easy it is to hide crimes and questionable behaviour at sea. Here be monsters.

Worth reading? Yes.

Worth re-reading? Yes.