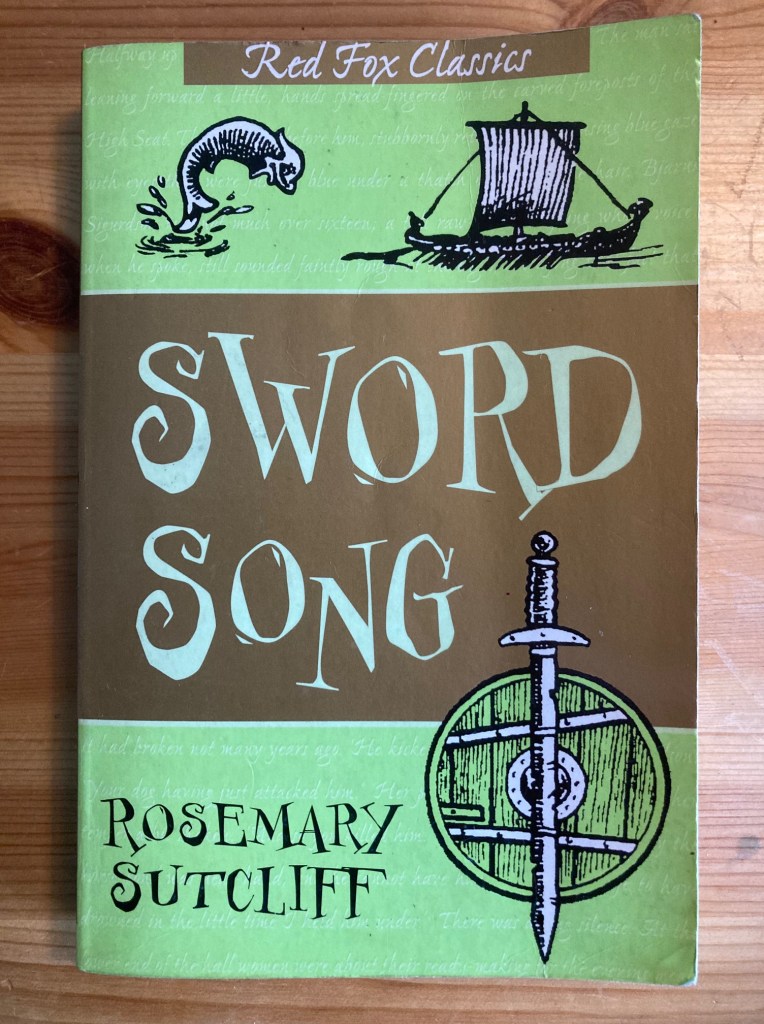

Rosemary Sutcliff, 1997

Red Fox Classics, 2001

272 pages

Read December 2023

Historical fiction, YA fiction

*Spoilers*

Bjarni, exiled from his settlement for five years for breaking an oath (and only indirectly for committing manslaughter), proceeds to make his way through the Viking world as a mercenary and sailor. What with being a solid Norse lad, this entails the expected abundance of seafaring and feuds. However, Sword Song was not entirely the picture of Viking life that I expected; Scandinavia is eschewed in favour of Viking settlements in the Celtic nations, and the non-martial aspects of Viking life, whilst not foregrounded, are given more space than I anticipated.

The slightly old-timey dialogue (‘Is it well with the bairn?’) and the use of placenames of yesterday (‘the Outer Isles’ for the Outer Hebrides and ‘Sutherland’ for the Highlands) lends it a feel of a time before lore, when homes were considered in a more fluid manner and certainly before the concept of a united kingdom. It is not always initially exactly clear where the story is taking place and I enjoyed this defamiliarisation, placing us in our protagonist’s calf-skin boots through five years of adventuring.

Its emphasis on adventure makes it a YA book (I mean, look at that front cover), although, while the violence is not gratuitous, nor is it shirked from. In Bjarni’s universe, whilst not a given, death by violent means is readily accepted. In other ways, the richness of details, especially on nature and boats, makes it a gratifying read as an adult: ‘Just where moorland fell away to machair a stream came down from the higher ground, pushing its way through a narrow glen suddenly and unexpectedly choked with trees-a-tangle, birch and rowan and willow and thorn’. This appeal to more considered tastes tempers the pace and prevents it from devolving into the monotony of just being sword fight after sword fight, which, conversely, is what I found hard work when I first bought this when I was 11 or 12 (RRP: £4.99) and sword fighting was a lot more important to me than bucolic vistas. Upon picking it up (20 years-plus later) I half-expected to DNF it again. Instead, I very much found the opposite: the break-up of the sword fighting is what helps make it a compelling read. The abundant descriptions of nature and place-setting that Sutcliff incorporates into her descriptions, without being overwrought, emphasises how these were peoples of the land and of the sea, and in a way, nation builders.

It feels well-researched, or at the least, convincingly researched, and both Norse and Christian mythology are touched upon, although they are not central to Bjarni’s worldview. These religions coexist, but primitive, brutal and tribalistic traditions abound in all wheres; feuds, funerals, how animals are treated, going into battle. With all of that said, the underlying zeitgeist is of an incremental shift from paganism to Christianity – the bigger picture paired with the individual experiences of Bjarni. Sutcliff also doesn’t shy away from incoporating the Vikings’ penchant for taking thralls – or slaves – and how some people did not have a chance to make their own way through the world.

I would have liked it if there had been a bit more introspection on Bjarni’s part: earlier on in the book ‘he was well enough content, though still there was an ache in him somewhere like the ache of an old wound when the wind is from the east’, but this is pretty much it. He seems to take five years of what seems to be regularly scheduled drama in stride, and is apparently content to wander with rarely a trace of homesickness.

Towards the end, he reflects upon how his people call home wherever they lay their head:

And suddenly, he was realising something that he had not realised before; that while he come of a people who could uproot easily, whose home was as much the sea as the land [Anghared] was of another kind […] She was flung out into a strange world that held nothing familiar, a cold place; he could feel the cold in her.

But there is little talk of how this strange, cold world has affected him. How has he changed by the end? I’ve not read any of Sutcliff’s other books, but as this was published post-humously (I don’t know if that included any of the writing and editing process), I suspect that this may have contributed to this slight sense of underdevelopment.

Worth reading? Yes.

Worth re-reading? Yes.