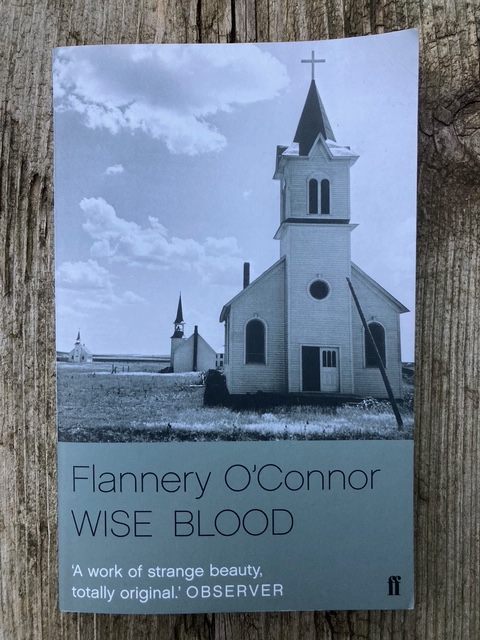

Flannery O’Connor, 1952

Read: June 2025

Edition read: Faber and Faber, 2008, 160 pages

Southern Gothic

*Spoilers*

The demobbed Hazel Motes returns to the Deep South to set up his own church, ‘The Church Without Christ’ circa late 1940s, relocating to the big (fictional) city of Taulkinham from his now-abandoned rural hometown after finding that his family has all died or moved away.

Set on becoming a preacher until conscripted at 18, Mote set himself on becoming an atheist – or anti-religion – preacher, seemingly out of a sense of nihilism. However, it’s not the ordeal of war, and his resulting injury, cause this crisis of faith; he’s just told that he doesn’t have a soul by a fellow GI.

There is a certain class of purportedly ‘classic’ novels that I am not struck by, and the common factor behind my lack of comprehension seems to be, why are these people doing these things?

This was my first problem with Wise Blood; the protagonist is told that he doesn’t have a soul and he switches from knowing ‘by the time he was twelve years old that he was going to be a preacher’ to wanting to ‘be converted to nothing instead of to evil’.

It was this inscrutable nihilism which reminded me of The Outsider. I generally go in for Southern Gothics (William Gay, Harry Crews and Cormac McCarthy are favourites of mine), but I was underwhelmed in a way that reminded me of Albert Camus’s The Outsider, where the weight of expectations brought too much baggage. That’s not to say Wise Blood didn’t have both good and great scenes (in particular, the ending), just that there were elements and sections which didn’t land, such as when Enoch Emery, whose role as a character seems to be a metonym for the (religious) masses, finishes his part in the story out in the woods dressed up as an ape. Given that it is he who is of the ‘wise blood’, following it to make his decisions, is this just a critique of idolatry?

It’s certainly misanthropic, with few characters coming out of this looking good; the blind preacher Asa Hawkes turns out to be a fraud and as soon as Motes sets up his religion, the conman Hoover Shoats duplicates it in order to make money. Emery certainly introduces an element of the grotesque – dressing as an ape, stealing a preserved corpse – as well as comedy (such as his mispronunciation of ‘museum’).

Another element that I couldn’t work out was Asa Hawkes’s daughter, Sabbath Lily; I think she is supposed to be predatory, but Motes never seems particularly victimised by her. What was interesting was how it ended with Motes’ landlady trying to find meaning in his – now blind – eyes, at the moment of his death, searching hard and finding nothing – or maybe just whatever she wants to find. Overall, however, if this is a parable on organised religion, I’m not sure what the lesson is.

Worth reading? Yes, but I didn’t like it as much as I wanted to.

Worth re-reading? No – with the caveat that it is hard to fully understand on a first read. A short and quick read at 160 pages, I think a second read would bring more out of it.