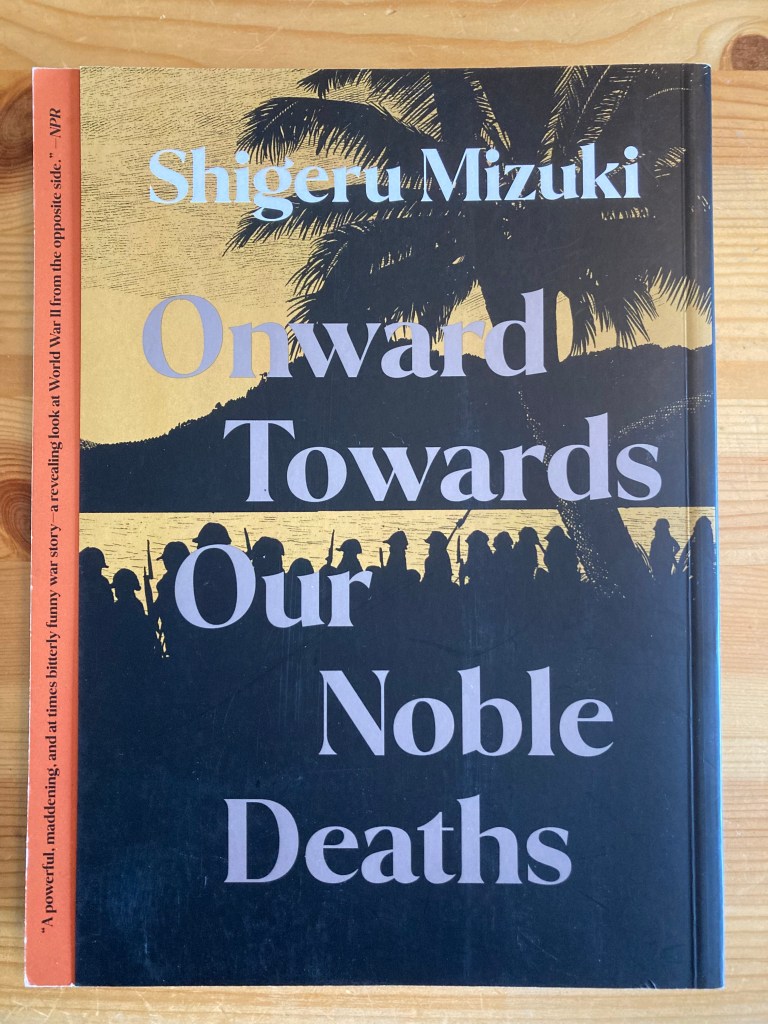

Shigeru Mizuki, 1973 (translated by Drawn & Quarterly in 2011)

February – May 2025

Page count: 372

Graphic novel

Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths is a semi-autobiographical, black-and-white graphic novel about a battalion of Imperial Japanese infantry who were commanded to hold New Britain, an eastern island of Papua New Guinea, in 1943, against approaching US forces.

It dissembles the image of the Imperial Japanese Army as being entirely made up of fanatics; the main characters are conscripts (‘rookies’), who are poorly trained, clumsy, grumble and are subject to abuse from their commanders, including physical beatings for no reason. Shigeru depicts these commanders with little sympathy; they are largely sadistic and inept, and refuse to recognise the strategic advantage that a guerrilla war – as opposed to the culminating banzai charge – would offer. The rank-and-file come across as most likely happy to surrender if they hadn’t been commanded to die fighting and told by their ranking superiors that to live would be dishonourable.

In the spirit of its original language and country of publication, it is printed in reverse, read right to left. The style combines somewhat quirky figures – heads and limbs fly from explosions and there are ‘BOOM’ onomatopoeias – with the naturalistic and textured backdrops of the rainforests of Papua New Guinea. This is, until the panels that depict the aftermath of conflict, where the death and destruction is no longer semi-comic and more like inked versions of war photos; prone bodies, trees shorn off, clouds of black smoke. The closing scenes switch exclusively to the photo-realistic drawing-style for these couple of pages, as if to say, what a waste.

There are lots of characters – enough for a dramatis personae to be provided at the the beginning – who begin to die at a rapid rate as US planes, tanks and troops close in. The US soldiers, when they arrive, are depicted with so few details as to come across as Green Army Men, but as much of the Japanese soldiers’ fight is with malaria, rationing, clean water and sadistic officers.

It is hard keeping up with so many characters at times, and placing who is who on first read-through; the only character arc to speak of is of a doctor who ends up openly questioning his superiors’ morality. Fewer characters, with fuller characterisation, would have made this clearer. Likewise, the narrative direction is not always clear, and occasionally details are elided; one situation suddenly leads to the next with no transition presented. On second read-through, this does come to feel like part of the unclear, disorientating experience, but this could have still been delivered with a slightly more considered narrative.

Obviously, depicting the perspective of Axis troops is to venture out onto thin ice, but this feels less like a justification than a exposé of the abundance of pointless death. One of the few humane officers feels compelled to commit suicide as he did not die in the first charge, and two others are ordered to commit seppuku – one of whom beforehand tears up a keepsake letter into the sea, which turns out not to even be from a girlfriend, but from his mum. On multiple occasions the infantry break into song; ‘Can’t hate the hateful enemy/forced to smile for smug soldiers/why am I stuck working this shitty job/no way out/all for my country’; as they sing this just before making their final charge, panel by panel they are shown simultaneously breaking down into tears.

It’s not a comprehensive look at the Imperial Japanese Army during World War Two, instead focusing on the author’s experience in the Imperial Japanese Army. He writes himself in as one of the characters, with the key, unsparing difference that instead of just losing an arm and contracting malaria, as he did in real life, the character survives a mauling in the suicide charge, only to be shot by an American soldier. A noble death indeed.

Worth reading? Yes.

Worth re-reading? Yes – the added clarity allows the poignant moments to come across more clearly.

I wonder if surviving the suicide charge wasn’t, rather than an act of cowardice, one final act of resistance as a human being.