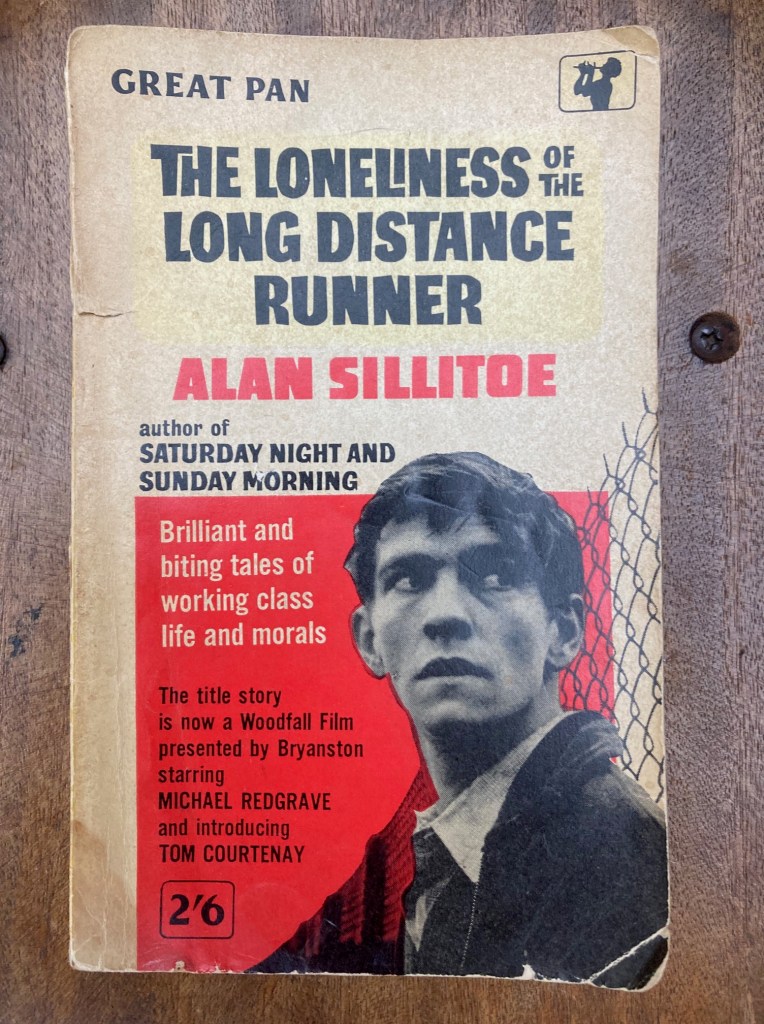

Alan Sillitoe, 1959

Read: September-October 2025

Edition read: Pan Books, 1961 (original price: two and a half shillings), 189 pages

Short-story collection, Realism

*Spoilers*

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner was recommended as an accompanying text whilst I studied Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. I didn’t get around to it before graduating, or that decade, or before a young angry man phase myself,* but that wasn’t for lack of enjoyment of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning; besides its snapshot of a (sometimes) angry and (quite often) rebellious character, I enjoyed its complexity and how it tested my assumptions about working-class literature. The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is a series of short stories by Alan Sillitoe that cover the similar grounds of disillusion within and rebellion against post-World War Two Nottingham society – which here, is urban, poor, oft violent and subject to officious authority.

These characters – who are men, generally young, but not always angry – have enough to scrape by. Some of them have even attained a degree of economic security. But they never have enough to have become aspirational. Very much aware of their place in society, they are cynical enough to be rebellious rather than revolutionary, typified by the climatic action of the protagonist of the eponymous story. The one mention of socialism comes from a factory worker’s middle-class wife, while the factory worker himself is too tired after a day of work to engage in any talk of politics.

Socially alienated and with bleak prospects, there is lots of petty crime (mostly theft) – but also some more measured slices of life, such as Mr Raynor the Schoolteacher, The Fishingboat Picture and Noah’s Ark. Nothing terrible happens (at least, not in the foreground of the stories), but neither does anything wonderful. This is a lot in life which the characters, except for the more rebellious ones, accept stoically. In Noah’s Ark the naughty children sneak their way into having a free go on a fairground ride. Even at this young age, they have already figured out that deception alone will get them ahead, and even then, fleetingly, in an otherwise hardknock life.

Sillitoe is a deft and observational writer, capturing unusual events in unremarkable environments. Besides capturing the Nottingham accent (‘“We’ve spent all our dough,” he said, “and don’t have owt left to go on Noah’s Ark wi”’) there are some clever premises for stories – such as the lack of agency in life bleeding over into a failed suicide attempt (On Saturday Afternoon), and how the protagonist ‘disappears’ and reappears during his telling of The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale. The quizzical nature of The Fishingboat Picture means that it doesn’t initially seem to have a point of entry, whether on a literal and subtextual level. Whilst it wasn’t my favourite, a couple of reads revealed it to be a commentary on the untidiness and complexity of relationships and how compromise sometimes gets us by.

The closing story, The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller (actually followed by a long poem, The Rats) is the protagonist’s childhood memory of playing soldiers with a local man of around 20 who has learning difficulties. The social dynamics of the angry young man movement are absent; this is just a scrappy childhood memory, with a poignant open-endedness to it:

‘I watched him. He ignored the traffic lights, walked diagonally across the wide wet road, then ran after a bus and leapt safely on to its empty platform.

And I with my books have not seen him since. It was like saying goodbye to a big part of me, for ever.’

*More cross than angry, really. Here’s to austerity – we did more with less and we were all in it together!