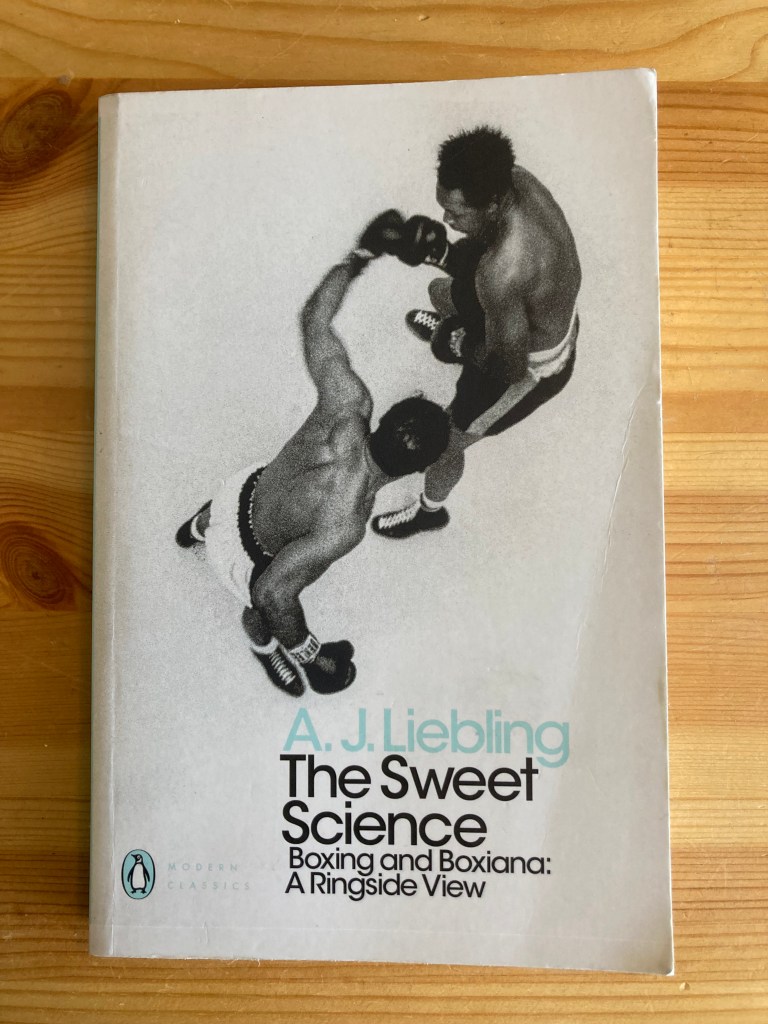

AJ Liebling, 1956

Read: January – April 2025

Edition read: Penguin Modern Classics 2018, 232 pages

Non-fiction

Liebling was a sports correspondent and this book was originally a series of articles for The New Yorker.

Liebling covers a multitude of fights spanning – from what I could figure out – 1951 to 1955, over 18 articles (it’s hard to say how many fights exactly, because he refers to historic fights – some of which predate him – on a regular basis). These fights include boxers who are considered to be some of the best ever: Sugar Ray Robinson, Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Willie Pep, Sandy Saddler and Joe Walcott. As such, this is widely considered to be a classic of boxing literature.

The old-timey, black-and-white quality comes off the page; sometimes this is charming, sometimes it feels dated. Liebling, as befitting a writer for The New Yorker, has an elaborate vocabulary, which at times comes across as archaic (such as the use of ‘milling coves’) or stuffy (just because you can use a French phrase, doesn’t mean that you must*). He does also write with great sarcasm at moments. Largely set in New York, many of the figures read like a Looney Tune character; this is not necessarily a criticism of the writing, but at points some of the dialogue reminded me of Bugs Bunny (‘waidle you read the papers tomorrow’), which does make it hard to take seriously.

Nonetheless, The Sweet Science remains a valuable insight into a particular period and captures what Liebling accurately believed to be a vanishing world. By the fourth paragraph of the introduction, he has already raised his contention that TV was killing off boxing for the sake of advertising (hence his repeated references to beer and razor blades at any opportunity). With that said, he regularly goes to what he readily depicts as sold-out fights, such as Rocky Marciano versus Archie Moore – as captured in his many descriptions of crowded New York streets, bars, venues, restaurants and gyms. These pieces also show his obsession with boxing; no dilettante, he goes to sparsely attended fights as well as the sold-out ones (hence the subtitle).

Liebling takes on the unenviable task of describing different boxing styles, although he perhaps reads a bit too much into the physique of fighters. As with Norman Mailer’s The Fight, this always extends to covering the exact shade of black fighters’ skin.

Of course, Liebling didn’t know that he was writing in what is now considered one of boxing’s golden ages, and often seems somewhat underwhelmed. It is interesting that Liebling denounces aspects of this era.

Ultimately, its dated nature made it hard to read at points. If you stick with it, it is an interesting snapshot into boxing and where it sat within society. In this sense, because of these flaws, it is comparable to Mailer’s The Fight.

Worth reading? Yes, although it is dated.

Worth re-reading? No.

* Besides boxing, apparently Liebling loved eating and writing about French food. An improbable pairing.